Getting Started with Difficult Conversations

Table Talks: Tips for Bold Conversations

The webinar is designed to provide considerations and practical tips to have more constructive conversations. We will focus on how to find commonalities among our differences and the benefits for us and our communities in working through our differences. Download webinar resources.

How to Begin

Try to think of the last time you had a conversation that was not easy: How did you feel before you began talking? How did you feel once the conversation ended? Did you accomplish your goals? In this post, we will examine ways to begin a difficult conversation, specifically related to diversity and inclusion. Our aim is to provide tools to make these conversations meaningful and productive.

Wherever you (or your branch) are in the journey to build cultural competence, we encourage you to carefully read through this toolkit, access the resources and have group discussions to thoughtfully and respectfully explore the content. Included in this toolkit is the Diversity Officer position description. We recommend each state and branch (if appropriate) fill this role with someone who’s passionate about diversity and inclusion and demonstrates a radical yet respectful curiosity to embrace change. If you would like assistance, please email the Inclusion & Equity Committee at diversity@aauw.org

Setting Ground Rules

One of the most important steps to an effective conversation about diversity and inclusion is to set ground rules for the participants. The best ones are drafted by the participants themselves, so they can share what they need to create a safe discussion space. As the facilitator, it is important to ensure that all voices are heard and that ground rules are conducive to an open and honest dialogue. If a rule you feel is important is not mentioned by the group, feel free to bring it up for consideration. Common ground rules include:

- Listen actively — respect others when they are talking.

- Speak from your own experience instead of generalizing (“I” instead of “they,” “we,” and “you”).

- Do not be afraid to respectfully challenge one another by asking questions, but refrain from personal attacks — focus on ideas.

- Participate to the fullest of your ability — community growth depends on the inclusion of every individual voice.

- Instead of invalidating somebody else’s story with your own spin on her or his experience, share your own story and experience.

- The goal is not to agree — it is to gain a deeper understanding.

- Be conscious of body language and nonverbal responses: They can be as disrespectful as words.

Ground rules may also include participation-management techniques. Do group members want to be called on or would they like to speak freely? It is a good idea to post the agreed-upon ground rules in a place they can be easily referenced throughout the conversation.

Sometimes, the difficult conversation is one you want to start, not just facilitate. Ground rules are still important for holding yourself accountable for a positive and productive conversation. Conversation ground rules can be found here.

Regardless of the forum, conversations about diversity and inclusion can be difficult. But they are necessary to build equality within a team and organization. Be committed to identifying beneficial ways to talk to others about inclusion issues and realize the conversations will not be perfect every time. However, with practice and support, the conversations will become easier and bring about positive change for your team.

Readings:

- Print Materials:

- Beaulieu, Sarah. Breaking The Silence Habit: a Practical Guide to Uncomfortable Conversations in the #Metoo … Workplace. New South Wales, Australia: Read How You Want, 2020.

- Hollins, Caprice D., and Ilsa M. Govan. Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion: Strategies for Facilitating Conversations on Race. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

- Oluo, Ijeoma. So You Want to Talk about Race. New York, New York: Seal Press, 2019.

- Strickland, Tessa, Kate DePalma, and David Dean. Children of the World. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Barefoot Books, 2018.

- Websites:

- Guidelines for Discussing Difficult or High-Stakes Topics

- Creating Brave Conversations about Diversity and Inclusion at Work

- Managing Difficult Classroom Discussions

- Here’s how we can discuss diversity and inclusion without confrontation

- How to Start the Conversation about Diversity & Inclusion

- 5 Tips for productive conversations about diversity

- How to Start the Conversation about D&I in 2020

- Effective Workplace Conversations on Diversity

- How to Have that Tough Conversation about Diversity and Inclusion

- Inclusion Discussion Starters

Activities:

- For Students:

- Fun Activities to Spark Conversations about Racial Diversity (Geared toward conversations with children)

- Diversity Discussion Starters

- Diversity and Inclusion Activities

- Diversity and Inclusion in the College Classroom

- For the Workplace:

- Diversity & Inclusion: Starting the Conversation

- Multiple resources on how to facilitate discussion, diversity and inclusion activities

- Santa Cruz Country Diversity Center (Has virtual support groups and activities for a wide audience)

- 6 Practical Diversity and Inclusion Activities You Can Start Today

- 5 Diversity and Inclusion Activities to Build Belonging on Teams

Videos:

- Hobson, Mellody. “Color Blind or Color Brave?” May 5, 2014. TEDTalk, Vancouver, BC. MPEG-4, 14:14.

- Smooth, Jay. “How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Discussing Race.” November 15, 2011. TEDxHampshireCollege, Amherst, MA. MPEG-4, 11:56.

- Grant, Risha. “How to have a Diversity and Inclusion Conversation.” June 24, 2020. Eagles Talent: online live stream, HTML5, 26:05.

- Kratz, Julie. “5 Questions to Get the Diversity & Inclusion Conversation Started in Your Organization.” Next Pivot Point: YouTube, HTML5, Video Series.

Community Agreements

Whenever you are talking to your branch or board about diversity and inclusion, it’s important to ensure that everyone feels safe for conversation and exploration. Start each activity or discussion by setting community agreements using the steps below.

Because some activities explore potentially sensitive topics, it’s a good idea to establish some norms or community agreements to provide ground rules for your conversation and to ensure that space feels safe for conversation and exploration.

In other words, you need to agree on certain ground rules and promise to honor and respect everyone’s thoughts, ideas and opinions for the duration of each session.

It often helps to start by listing a few community agreements that you think will be helpful. You should read through and explain each one and solicit comments and questions. Then, ask if the participants have any to add.

Before the meeting, prepare a flip chart sheet with “Community Agreements” written at the top, followed by the sample community agreements:

- Speak from the “I” perspective: Avoid speaking for others by using “we,” “us,” or “them.”

- Listen actively: Listen to understand, not to respond. Sometimes we are tempted to begin formulating what we want to say in response, instead of giving 100 percent of our focus to the speaker. So let’s make sure we are listening 100 percent.

- Step up, step back: If you usually speak up often or you find yourself talking more than others, challenge yourself to lean in to listening and opening up space for others. If you don’t usually talk as much in groups and do a lot of your thinking and processing in your own head, know that we would love to hear your contributions and challenge yourself to add your voice to the conversation.

- Respect silence: Don’t force yourself to fill silence. Silence can be an indication of thought and process.

- Share, even if you don’t have the right words: Suspend judgment and allow others to be unpolished in their speaking. If you are unsure of their meaning, ask for clarification.

- Uphold confidentiality: Treat the candor of others as a gift. Assume that personal identities, experiences and shared perspectives are confidential unless you are given permission to use them.

- Lean into discomfort: Learning happens on the edge of our comfort zones. Push yourself to be open to new ideas and experiences even if they initially seem uncomfortable to you.

Remember, after you read through this list, ask if anyone has comments or questions about the community agreements overall. Then ask if anyone has something to add to the list. Take responses and add them to the list. Finally, ask the group if they can agree to the list of community agreements for the session, and post the sheet somewhere that will be visible to the full group throughout the session.

Managing Conflict

Conflict is normal and can be inherent in nearly every situation. When conflict arises, what matters when is how we deal with it. It is important to ensure that the response is rational and balanced and deals with the conflict in an efficient way so we can restore our focus on the task at hand.

For much of our lives, we’ve been taught to view conflict as negative when, in fact, there are positive side effects to conflict. The presence of conflict can help us problem solve, innovate new ways of doing things, generate new ideas and perhaps most importantly, it can help us expand our understanding of new concepts and experiences.

Now, just to be clear: We are not saying that conflict is good per se. Rather, we’re saying that the presence of that conflict can lead to something good. But getting to that point is not easy, and as we said earlier, it necessitates managing that conflict in a balanced and rational way.

So how do you do that? Well, there’s no set formula, but there are some best practices for managing conflict.

Best Practices for Managing Conflict

- Attempt to pursue a common goal, rather than individual goals.

- Openly and honestly communicate with everyone.

- Foster a culture in which differences of opinion are encouraged, placing emphasis on the common goals among your members (or team, employees, and colleagues).

- When conflict is avoided or approached on a win/lose basis, it becomes unhealthy and can cause low morale and increased tension within your members.

Understanding Your Way of Dealing with Conflict

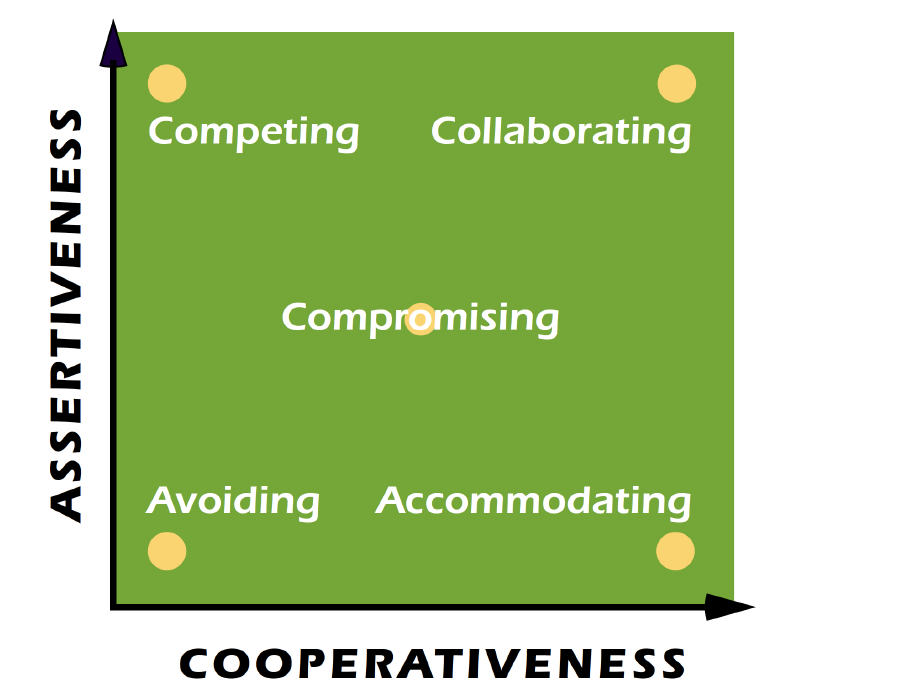

In the 1970s, a model for understanding managing conflict was created and from it the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI) was born. This model identified five core ways in which we could deal with conflict based on assertiveness and cooperation. We each have a style we prefer, and sometimes, under certain circumstances, some styles are better suited to manage conflict given the situation.

The five styles are:

- Collaborating Style

- Competing Style

- Avoiding Style

- Accommodating Style

- Compromising Style

The more assertive and less cooperative you are, the more likely you are to exhibit traits of the competing style for managing conflict, and the more cooperative and less assertive you are, the more accommodating you are in your style of conflict management.

Readings:

- Print Resources:

- Coleman, P., Deutsch, M. and Eric C. Marcus., The Handbook of Conflict Resolution: Theory and Practice (3rd Edition). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2014.

- Mayer, B. The Dynamics of Conflict Resolution: A Practitioner’s Guide. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2000.

- Mitchell, B. and Cornelia Gamlem. The Conflict Resolution Phrase Book. Wayne, NJ: Career Press, 2017.

- Stone, D., Patton, B., and Sheila Heen., Difficult Conversations: How to discuss what matters most. New York: Penguin Group, 1999.

- Websites:

Activities:

- For Students:

- For the Workplace:

Videos:

Related

Key Terms & Concepts

Dimensions of Diversity & Identity

Diversity Structure & Planning

Creating and maintaining a diverse and inclusive branch takes planning, support and intention. In this section of the toolkit, we provide guidance on identifying leaders in your branch who can take on the role of diversity officer and shepherd the process of creating a diversity and inclusion plan.