Q&A with AAUW Coretta Scott King Fellow Nell Painter

Opening Eyes

What we see depends heavily on what our culture has trained us to look for.

After retiring from Princeton University following a celebrated teaching and scholarship career in history, AAUW Coretta Scott King Fellow Nell Irvin Painter did something no one saw coming: she began a second career as an artist.

While art was a longtime passion for Painter, this change was more than a hobby to fill her time in retirement. Having already earned a doctorate in history from Harvard University, during which time she received the AAUW fellowship, she returned to school to build her new career. She earned a bachelor of fine arts from the Mason Gross School of the Arts at Rutgers University and then a master of fine arts from Rhode Island School of Design.

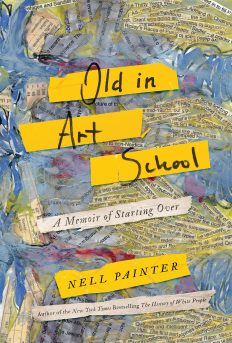

Painter uses found images and digital manipulation to reconfigure the past through art. Her new memoir, Old in Art School, reminds us all that it’s never too late to reinvent yourself. The book, reviewed by the New York Times and NPR and featured on Oprah’s list of O’s Top Books of Summer, was released on June 19, 2018. We had a chance to catch up with Painter recently to talk about her journey.

After a busy first career, what made you decide to go back to school for your master of fine arts?

I had been creeping into visual culture for quite some time where text failed me, starting with Sojourner Truth: A Life, a Symbol. (Truth did not read or write.) Then came Creating Black Americans, which I illustrated with black fine art. Two introductory painting classes at Princeton and the drawing and painting marathon at the Studio School in New York showed me my interest and physical strength were equal to the challenges of something new.

What inspired you to write Old in Art School?

What inspired you to write Old in Art School?

At first it was friends and colleagues’ curiosity. They wanted me to send back a report of my experiences. I love to write, so I took that on. Then I was enjoying the note-taking [so much] that I kept going beyond the initial impetus of answering how it felt to leave a Princeton chaired professorship.

What does being an artist mean to you? How does it differ from the other professional identities that you’ve been known as for most of your life?

For me, the biggest conceptual difference lies in art making’s freedom from the need to tell the truth. I know many other artists see their work as a means of telling the truth about society and history. I’ve already done that in my books, so I just do whatever I want to visually, whether or not it comments on the world. I don’t ask my art to make sense.

This is all complicated by the outsized presence of my previous books, especially The History of White People. That book continues to inspire my art. And people still want me to talk about it. I do, kind of as my day job.

What was the most challenging part of this new chapter in your life?

There were challenges galore, from seeing myself through other people’s eyes as just an old black woman of little interest or importance, to dragging my 20th-century eyes into the 21st century. Prevailing aesthetics in art making changed enormously while I was preoccupied by history. I had to realize that and adjust to it.

What advice would you give to women who want to reinvent themselves?

First, see to your health and your finances, as reinvention can be physically strenuous and financially expensive. Make sure the people who depend on you — parents, children, grandchildren, spouses — are reasonably well settled and supportive. Then start the pursuit of your new course by informing yourself about it. This usually means taking courses, though it can also mean apprenticeship.

AAUW's wall features a framed photo of you and Coretta Scott King. What did that fellowship mean to you?

I haven’t seen that photo in years, though it still has a place in my mind’s eye. I remain grateful for AAUW’s vote of confidence in me very early on and for the lovely opportunity of meeting Coretta Scott King. [See thank you note from Coretta Scott King.]

Though very welcome, this award came to me as a surprise, for before AAUW’s award I had not thought of myself as part of the community of American university educated women. I grew up in the 1940s and 1950s, when I assumed such organizations were lily white unless specifically stated otherwise. That’s how American society was back then, and much of it remains so today. People have to make specific statements, take specific actions, to establish the openness of American institutions. It can’t be taken for granted.

Americans have to take conscious steps to educate themselves on the automatic biases in our society if institutions are to become truly inclusive. It’s a lot of work, I know. I hope this work can be done.

What is your next project?

I’m not sure of my next project, which I can’t turn to in a serious way until 2019, after this spate of book promotion. Something is bubbling up in my consciousness, however; an artist’s book on the history, historical memory, visual presence, and heritage tourism of Emmett Till. These thoughts — not nearly coherent enough to be called a project — started rolling around in my head after the uninformed brouhaha over Dana Schutz’s painting of Till in last year’s Whitney Biennial. I could bring to bear my historiographical and artistic strengths in a work I would both write and visualize. We’ll see if I have the strength to follow through.

Thank you for taking the time to talk!

Thanks for your support long before such support could be routinely imagined and for your interest in my memoir. Both mean a lot to me, then and now.

Related

Funding Women’s History

Fast Facts: Women of Color in Higher Ed