AAUW : Empowering Women Since 1881

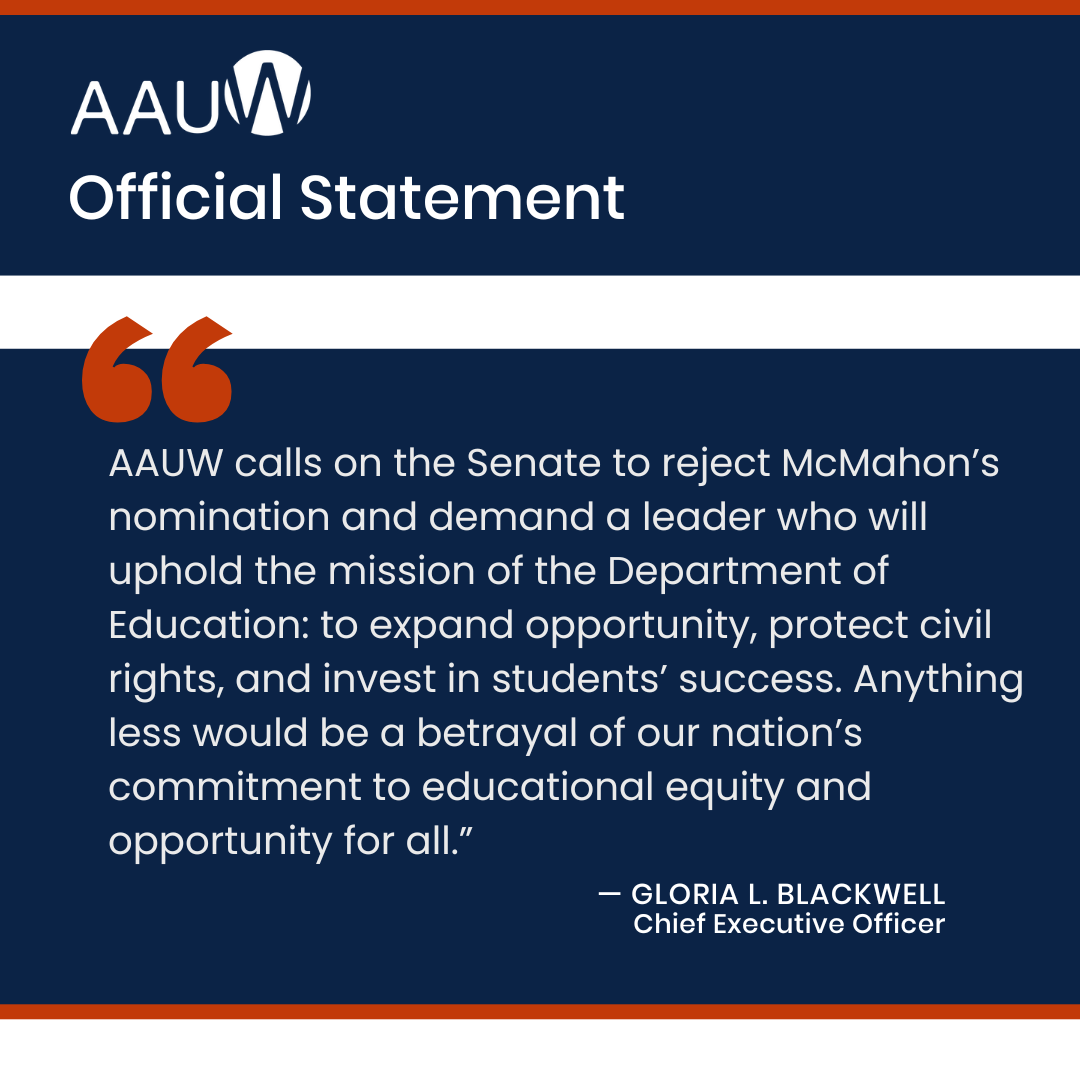

AAUW Strongly Opposes Linda McMahon’s Nomination for U.S. Secretary of Education

AAUW condemns the nomination of Linda McMahon for U.S. Secretary of Education, citing concerns over her lack of experience in public education and commitment to students’ rights. Students deserve a leader who prioritizes equity, accountability, and access to quality education.

AAUW’s Annual Report: A Year of Impact

Discover how AAUW is advancing equity for women and girls nationwide. Our latest Annual Report highlights key achievements, financials, and the impact of our programs over Fiscal Year 2024. Be sure to check out AAUW’s stories of impact.

AAUW Denounces District Court’s Decision to Vacate Title IX Rules

The decision by the U.S. District Court in the Eastern District of Kentucky to vacate the updated Title IX rules makes it easier for schools to dismiss cases, harder to hold perpetrators of sexual harassment and assault accountable, and more difficult for survivors to get the protections they need.

Students deserve better, and AAUW is prepared to fight on their behalf.

Securing the Future: A Post-Election Conversation on Women's Economic Security

Join us for an important webinar exploring the path forward for women’s economic security under the next U.S. President and the 119th Congress. Expert panelists include: Heather M. Boushey, Ph.D., 1997–98 AAUW American Fellow, economist and co-founder of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth Jamila K Taylor, Ph.D., President & CEO of the Institute for Women’s Policy Research Gloria L. Blackwell, CEO of American Association of University Women

Helpful How-tos

Start Talking about Pay!

8 Great Job Boards for Diverse Professionals

Tips for Getting Educational Funding

Take Action

Members of AAUW’s Action Network receive urgent email notices and text messages when their advocacy is needed most. With our online Two-Minute Activist tool, it takes just minutes and an internet connection to make your voice heard on issues impacting women and girls!